This post is a response to the esteemed New Testament scholar N.T. Wright’s TIME article, ‘The New Testament Doesn’t Say What Most People Think It Does About Heaven’, published in December 2019.

In this article, Wright argues that the widely held belief of many Christians today – that the faithful will go to heaven after they die – is not reflective of the beliefs of “the early Christians”. Wright makes some excellent points throughout, exposing readers to many verses in the New Testament that do not fit this widely held model. However, I see Wright’s article as potentially overreaching in his rebuttals against, and ignoring, many of the verses most often used to support the alternative – that some “early Christians” did indeed believe such a thing.

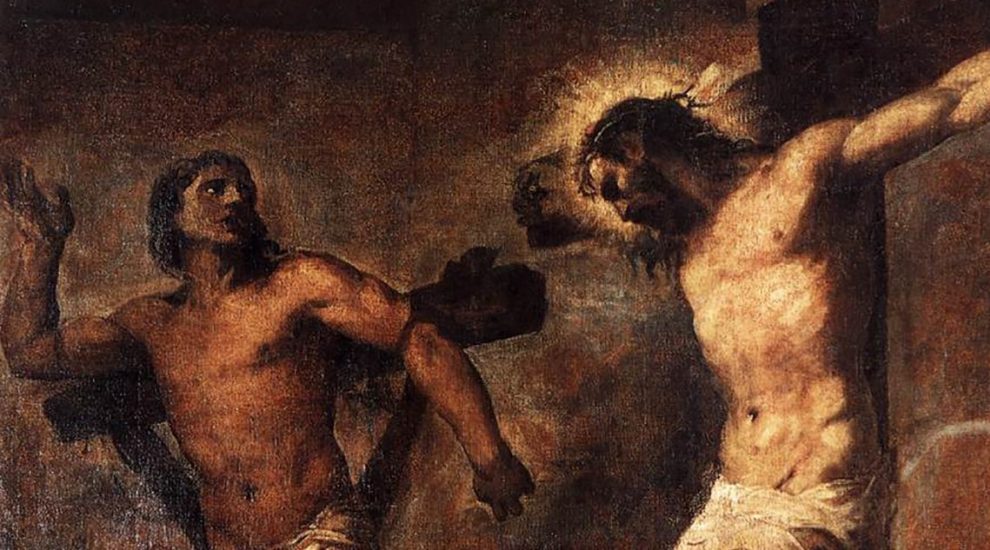

“Today You Will Be With Me in Paradise…”

Contrary to Wright, I think Luke 23:43 – where Jesus tells the faithful bandit crucified alongside himself that “today you will be with me in paradise” – is an example of “early Christians” thinking they would go to heaven after they die.

[Before I proceed, let me first acknowledge that the verse is obviously not historical. As is well known, the saying has been put onto the lips of Jesus. It is a clear example of Luke’s re-writing of his primary source, the Gospel of Mark. As such, the verse is clearly secondary. However if we are defining “early Christians” to be those living within the period of the composition of the New Testament, as Wright seems to, then Luke’s re-writings still count as reflective of beliefs of “the early Christians”]

Wright tones down the passage’s most immediately obvious interpretation – that Jesus is telling the bandit he’s about to go to heaven – by suggesting that Jesus is instead talking about some sort of “blissful rest”. But if that is the case, it is curious that Luke’s Jesus was not clearer on this point. Perhaps “today you will sleep, but on that coming day of resurrection you will be rewarded” would have been more appropriate and equally succinct? But that is not what is recorded. What Luke has Jesus say fits seamlessly into the view Wright is attempting to argue against.

Presently Enjoying the Spoils of Abraham’s Bosom

Strengthening this idea that at least some early Christians believed that the righteous would go to up to heaven immediately after death is a gospel parable found on the lips of Jesus which seems to presuppose such a thing. The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus found in Luke 16:19-31 is curiously overlooked by Wright in his article. In the parable, the righteous poor man Lazarus is “carried away by angels” to heaven, enjoying the spoils alongside Abraham, all while the unrighteous Rich Man suffers in flames in Hades (Hell). That the Rich Man looks “up” and pleads to Abraham to send Lazarus to his brothers to warn them of the horrors of Hell shows that these events are not supposed to be in some ‘post-renewed-Earth’ era as Wright’s “early Christians” are supposed to only have believed. While it is true that the scene is told as a parable, and as such was not necessarily intended to be taken as an actual occurrence, the genre of parables was usually not one of science-fiction. Parables tended to reflect common understandings of the cosmos. If some early Christians did not believe that their ultimate fate would be their souls being taken to heaven soon after death, it is curious that some early Christians (and potentially the Historical Jesus himself) composed parables that seemed to presuppose such a thing.

An Imminent Rapture in the Earliest Sources

Wright also overlooks 1 Thessalonians 4:17-18 in the article, a passage from the earliest surviving Christian text. There, Paul states that on the great Parousia day (a “day” he mistakenly believed was imminent) that “We [the remaining and recently-risen faithful] will be caught up in the clouds […] to meet the Lord in the air, and so we will be with the Lord forever”. The place where one is to “be with the Lord forever” seems to be “up in the clouds”. Mark 13:26-27 (also ignored in Wright’s article) also speaks of coming angels from “the clouds” to “gather” the elect “from the ends of the earth” – a surely synonymous conceptual event as the one described by Paul.

Wright’s handling of Philippians 1:23 and linking it alongside John 14:2 seems similarly questionable. There’s nothing in Paul’s stating that his “desire is to depart [i.e. die] and be with the Messiah, for that is far better” to suggest that Paul is thinking about some “waiting room”. Furthermore, even Wright’s translation of John 14:2’s Greek word μοναι to “waiting room” is suspect. The word just means an abode / lodging / dwelling-place / room / mansion. In 2 Corinthians 12:1-10, Paul describes having already once been taken “up” into the third heaven, which he describes as “paradise” (παραδεισω, the same Greek word used in Luke 23:43) – not as a “waiting room”. Paul is apparently conscious while briefly experiencing this paradise.

Conclusion – Wright’s Wrongs

Wright correctly understands that the texts in question need to be interpreted in light of their historical contexts in order to tease further historical insight from them about what the early Christians believed. One of the contexts Wright admits is an important lens through which to view the texts is that of “Greek thought”. Yet, as far as I can see, this admission somewhat undercuts his argument. On the one hand Wright wants to say that only contemporary ‘Middle Platonists’ believed in the kind of heavenly-fate he’s trying to argue against and that early Christians were not ‘Middle Platonists’. Yet ‘Middle Platonism’ is certainly a subcategory within “Greek thought”. So if “Greek thought” needs to be taken into consideration when interpreting verses like Luke 16:19-31, 23:43 or 1 Thessalonians 4:17-18, or Mark 13:26-27 (where the teachings seem to presume an ‘up there’ heavenly fate as opposed to a ‘down-here’ renewed-earthly one), ‘Middle-Platonic’ ideas about ascending to heaven after one’s death cannot be so easily dismissed. In other words, those passages make excellent sense had they arisen within that Middle-Platonic / Greek thought paradaigm that Wright seeks to downplay.

The mistake to make is to assume that the New Testament is necessarily consistent in its teaching on the fate of the faithful – that it either teaches one specific view or the other. Indeed, there is significant debate among Pauline scholars about the coherence of Paul’s thought (i.e. whether his epistles are consistent enough to warrant a systematization of his theology). I believe Wright is making the very mistake he is concerned others do when they “squash and chop” the New Testament to “fit their own expectations” – only from the opposite end of the theological tug-of-war rope. Wright’s misguided expectation is of a theologically consistent New Testament devoid of any of its writers having even the briefest moment of Middle-Platonic thought. To conclude, I think it’s easier to recognize that the New Testament expresses a variety of ideas on this issue of the fate of the faithful, some of which include the idea that Wright seeks to deny.